Environmental stress shapes every corner of our planet, influencing ecosystems, human health, and the delicate balance between survival and thriving in our rapidly changing world.

🌍 Understanding Environmental Stress: The Foundation of Change

Environmental stress encompasses the various pressures that natural and human-induced factors place on living organisms and ecosystems. From extreme temperatures and drought to pollution and habitat destruction, these stressors create cascading effects that ripple through biological systems, affecting everything from microscopic organisms to entire civilizations.

The concept of environmental stress isn’t merely academic—it’s deeply personal and profoundly relevant to our daily lives. When we experience a heatwave, witness declining wildlife populations, or struggle with allergies exacerbated by air pollution, we’re directly encountering the manifestations of environmental stress. Understanding these pressures helps us comprehend not only ecological transformations but also the fundamental connections between planetary health and human well-being.

Scientists categorize environmental stress into several primary types: physical stressors like temperature extremes and radiation, chemical stressors including pollutants and toxins, and biological stressors such as invasive species and disease outbreaks. Each category operates through distinct mechanisms, yet they frequently interact in complex ways that amplify their individual impacts.

The Biological Response: How Organisms Adapt to Pressure

Living organisms have developed remarkable strategies to cope with environmental stress throughout evolutionary history. These adaptive mechanisms range from immediate physiological responses to long-term genetic changes that enhance survival under challenging conditions.

At the cellular level, stress triggers intricate molecular pathways that activate protective proteins and antioxidants. Heat shock proteins, for instance, help stabilize cellular structures during temperature extremes, while specialized enzymes neutralize harmful reactive oxygen species generated under stress conditions. These microscopic defenses represent millions of years of evolutionary refinement.

Plants demonstrate particularly fascinating stress responses. When faced with drought, many species close their stomata to conserve water, redirect resources toward root growth, and produce protective compounds that prevent cellular damage. Some desert plants have evolved CAM photosynthesis, allowing them to collect carbon dioxide at night when water loss is minimal—a brilliant adaptation to extreme aridity.

Behavioral Adaptations: Nature’s Survival Strategies

Beyond physiological changes, organisms modify their behavior to minimize stress exposure. Birds migrate thousands of miles to escape harsh winters, fish move to deeper, cooler waters during heatwaves, and many animals adjust their activity patterns to avoid the hottest parts of the day. These behavioral flexibility mechanisms demonstrate the intelligence embedded within natural systems.

Humans, too, have historically adapted behaviorally to environmental pressures. Traditional architectural styles in different climates reflect centuries of accumulated wisdom about thermal regulation—from thick adobe walls in desert regions to elevated stilt houses in flood-prone areas. These time-tested approaches offer valuable lessons for contemporary climate adaptation strategies.

🏭 Human-Induced Environmental Stress: The Anthropocene Challenge

The industrial era has introduced unprecedented environmental stressors at scales and speeds that dwarf natural variability. Climate change, pollution, deforestation, and resource extraction have fundamentally altered planetary systems, creating novel pressures that challenge organisms’ adaptive capacities.

Carbon dioxide concentrations have risen from approximately 280 parts per million before the industrial revolution to over 420 ppm today—a change that occurred in mere centuries rather than millennia. This rapid atmospheric transformation drives global temperature increases, ocean acidification, and altered precipitation patterns that stress ecosystems worldwide.

Chemical pollution represents another critical stressor. Synthetic compounds that never existed in nature now permeate every environment, from microplastics in the deepest ocean trenches to persistent organic pollutants in Arctic ice. These substances disrupt endocrine systems, impair reproduction, and accumulate through food chains with devastating consequences for apex predators, including humans.

Habitat Fragmentation and Biodiversity Loss

Perhaps no environmental stressor threatens biodiversity more acutely than habitat destruction and fragmentation. When continuous forests become isolated patches separated by agricultural land or urban development, species face multiple compounding stresses: reduced territory size, decreased genetic diversity, disrupted migration routes, and increased vulnerability to predators and edge effects.

The Amazon rainforest exemplifies this crisis. Deforestation has transformed vast swathes of continuous jungle into a mosaic landscape where remaining forest fragments experience higher temperatures, reduced humidity, and increased fire risk. These edge effects penetrate hundreds of meters into remnant patches, fundamentally altering microclimates and species composition.

💚 Environmental Stress and Human Health: The Intimate Connection

The relationship between environmental stress and human well-being extends far beyond abstract ecological concerns. Air pollution alone causes an estimated seven million premature deaths annually, while climate-related disasters displace millions and exacerbate food insecurity across vulnerable regions.

Heat stress poses increasingly severe health risks as global temperatures rise. Urban heat islands—where concrete and asphalt absorb and radiate heat—create microclimates several degrees warmer than surrounding areas, disproportionately affecting elderly residents, outdoor workers, and communities lacking air conditioning. Heat-related mortality spikes during extreme weather events demonstrate our physiological vulnerability to temperature extremes.

Mental health consequences of environmental stress receive growing recognition from researchers and clinicians. Eco-anxiety—persistent worry about environmental destruction—affects significant portions of younger generations who face uncertain futures. Natural disaster survivors frequently experience post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety long after physical threats have passed.

The Healing Power of Nature Exposure

Paradoxically, while environmental degradation harms well-being, nature exposure provides profound health benefits. Studies consistently demonstrate that time spent in green spaces reduces stress hormones, lowers blood pressure, improves mood, and enhances cognitive function. This phenomenon, sometimes called “nature therapy” or ecotherapy, has prompted urban planners to prioritize parks and green corridors.

Forest bathing—the Japanese practice of mindful immersion in forest environments—has gained scientific credibility as research reveals measurable physiological improvements from woodland exposure. Phytoncides, aromatic compounds released by trees, appear to boost immune function and reduce stress markers, suggesting that forests offer more than psychological comfort.

🌱 Ecosystem Services Under Stress: When Nature’s Support Systems Falter

Ecosystems provide invaluable services that underpin human civilization: clean water, fertile soil, crop pollination, climate regulation, and natural disaster protection. Environmental stress degrades these services, often in ways that remain invisible until critical thresholds are crossed.

Coral reefs illustrate this vulnerability dramatically. These biodiversity hotspots support approximately 25% of marine species while occupying less than 0.1% of ocean area. They also protect coastlines from storm surges, support fisheries, and generate tourism revenue. However, thermal stress from warming oceans triggers coral bleaching—the expulsion of symbiotic algae that provide corals with nutrients and color. Repeated bleaching events have devastated reefs globally, compromising all their ecological and economic functions.

Pollinator populations face multiple simultaneous stressors: pesticide exposure, habitat loss, disease, and climate disruption. Since pollinators facilitate reproduction for approximately 75% of crop species and 90% of flowering plants, their decline threatens food security and ecosystem stability. The phenomenon highlights how environmental stress on one group cascades through interconnected systems.

Soil Degradation: The Silent Crisis

Healthy soil represents one of Earth’s most valuable yet underappreciated resources. This living matrix of minerals, organic matter, and billions of microorganisms per handful provides the foundation for terrestrial food production. However, intensive agriculture, deforestation, and erosion degrade soil at alarming rates.

Soil formation occurs gradually over centuries, while degradation can happen within years or even single growing seasons. When soil loses its structure, fertility, and biological activity, it becomes less capable of retaining water, supporting plant growth, and sequestering carbon. This environmental stress on agricultural lands directly threatens food security while contributing to climate change through reduced carbon storage.

🔬 Measuring Environmental Stress: Tools and Indicators

Quantifying environmental stress requires sophisticated monitoring systems that track multiple parameters across spatial and temporal scales. Remote sensing satellites provide global perspectives on deforestation, urban expansion, and vegetation health, while ground-based sensors deliver detailed data on air quality, water chemistry, and soil conditions.

Bioindicator species—organisms particularly sensitive to environmental changes—serve as early warning systems for ecosystem stress. Amphibians, with their permeable skin and aquatic-terrestrial life cycles, are especially vulnerable to pollution and habitat disruption. Declining amphibian populations often signal broader environmental problems before they become apparent through other measures.

Scientists have developed composite indices that integrate multiple stressors into single metrics. The Environmental Performance Index, for example, evaluates countries across environmental health and ecosystem vitality categories, facilitating international comparisons and policy assessments. Such tools help translate complex environmental data into actionable information.

🌊 Climate Change: The Multiplier of Environmental Stress

Climate change functions as a threat multiplier, amplifying existing environmental stressors and creating novel challenges. Rising temperatures stress organisms directly through heat exposure while indirectly altering precipitation patterns, growing seasons, and species interactions.

Ocean acidification—climate change’s “evil twin”—occurs as oceans absorb excess atmospheric carbon dioxide, forming carbonic acid that lowers pH levels. This chemical stress impairs shell and skeleton formation in marine organisms from plankton to mollusks, threatening the foundation of marine food webs. The speed of acidification outpaces anything in the geological record except mass extinction events.

Extreme weather events—hurricanes, droughts, floods, and wildfires—have intensified under climate change, subjecting communities and ecosystems to acute stress episodes. The 2019-2020 Australian bushfires burned over 18 million hectares, killing an estimated three billion animals and releasing massive carbon quantities. Such catastrophic events demonstrate how environmental stress can rapidly overwhelm both natural and human systems.

Feedback Loops and Tipping Points

Environmental stress can trigger feedback loops that accelerate degradation. Melting Arctic permafrost releases methane—a potent greenhouse gas—which drives further warming and more melting. Similarly, drought-stressed forests become more vulnerable to wildfires, which release carbon that intensifies climate change, creating conditions for more droughts and fires.

Tipping points represent thresholds beyond which systems shift to fundamentally different states, often irreversibly on human timescales. The Amazon rainforest may approach such a threshold, where continued deforestation and climate stress could transform it from a carbon sink into a savanna-like ecosystem, with catastrophic implications for global climate regulation and biodiversity.

🛠️ Mitigation and Adaptation: Responding to Environmental Stress

Addressing environmental stress requires complementary strategies: mitigation efforts that reduce stressor intensity and adaptation measures that enhance resilience to unavoidable pressures. Both approaches demand coordinated action across scales, from individual behavior changes to international policy frameworks.

Renewable energy transition represents crucial mitigation, replacing fossil fuels with solar, wind, and other clean sources to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Energy efficiency improvements—from LED lighting to building insulation—deliver immediate benefits while reducing resource consumption. These technological solutions must scale rapidly to achieve climate stabilization goals.

Nature-based solutions harness ecosystem processes to address environmental challenges. Wetland restoration filters water pollution, sequesters carbon, and provides flood protection. Urban tree planting reduces heat island effects, improves air quality, and supports mental health. Such approaches deliver multiple co-benefits while working with rather than against natural systems.

Building Personal and Community Resilience

Individual actions collectively shape environmental outcomes. Dietary choices, transportation modes, consumption patterns, and waste management practices all influence environmental stress. Plant-rich diets reduce agricultural land requirements and greenhouse gas emissions, while minimizing single-use plastics decreases pollution stress on ecosystems.

Community resilience emerges from social connections, local resources, and shared preparedness. Neighborhood networks that check on vulnerable residents during heatwaves, community gardens that enhance food security, and local energy cooperatives all build capacity to withstand environmental stresses while strengthening social fabric.

🔮 The Path Forward: Transforming Our Relationship with Nature

Addressing environmental stress ultimately requires fundamental shifts in how humanity relates to the natural world. The prevailing paradigm that treats nature as an inexhaustible resource to be exploited must evolve toward recognition of our embeddedness within, not separation from, ecological systems.

Indigenous knowledge systems offer valuable perspectives on sustainable coexistence with nature. Many traditional practices embody sophisticated understanding of ecosystem dynamics and resource management developed over millennia. Integrating these insights with contemporary science can generate more holistic and effective approaches to environmental challenges.

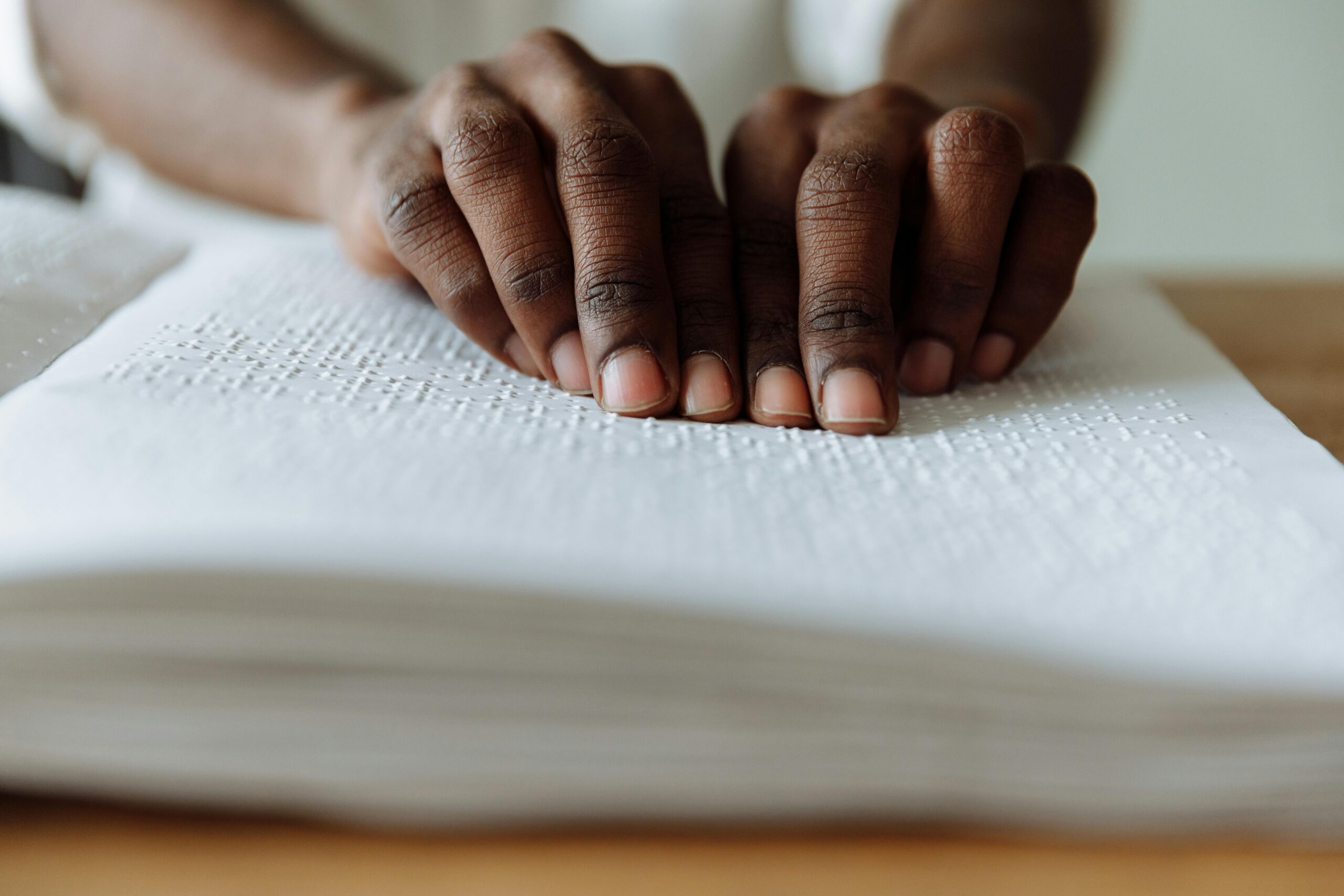

Education plays a pivotal role in fostering environmental stewardship. When people understand ecological principles and their connections to well-being, they make more informed decisions and support necessary policy changes. Environmental literacy should become as fundamental as reading and mathematics in preparing citizens for 21st-century challenges.

🌟 Embracing Hope Through Action

Despite daunting environmental challenges, numerous success stories demonstrate that positive change remains possible. The recovery of the ozone layer following the Montreal Protocol shows that international cooperation can address global environmental threats. Species brought back from the brink of extinction—from humpback whales to bald eagles—prove that conservation efforts work when adequately supported.

Technological innovation continues creating new tools for environmental monitoring, restoration, and sustainable production. Advances in renewable energy have made clean power increasingly cost-competitive with fossil fuels, while precision agriculture minimizes inputs and environmental impacts. Such developments provide grounds for cautious optimism if deployed rapidly and equitably.

The key lies in recognizing that environmental stress and human well-being are inextricably linked. Protecting ecosystems isn’t altruistic sacrifice but enlightened self-interest. When we safeguard nature’s resilience, we invest in our own health, security, and prosperity. This understanding can motivate the urgent, sustained action necessary to navigate environmental challenges and create a more sustainable future for all life on Earth.

Every individual possesses agency in shaping environmental outcomes. Whether through personal lifestyle adjustments, professional contributions, community engagement, or political advocacy, each person can participate in reducing environmental stress and building resilience. The cumulative impact of millions making thoughtful choices creates the transformative change our moment demands.

Toni Santos is a regulatory historian and urban systems researcher specializing in the study of building code development, early risk-sharing frameworks, and the structural challenges of densifying cities. Through an interdisciplinary and policy-focused lens, Toni investigates how societies have encoded safety, collective responsibility, and resilience into the built environment — across eras, crises, and evolving urban landscapes. His work is grounded in a fascination with regulations not only as legal frameworks, but as carriers of hidden community values. From volunteer firefighting networks to mutual aid societies and early insurance models, Toni uncovers the structural and social tools through which cultures preserved their response to urban risk and density pressures. With a background in urban planning history and regulatory evolution, Toni blends policy analysis with archival research to reveal how building codes were used to shape safety, transmit accountability, and encode collective protection. As the creative mind behind Voreliax, Toni curates historical case studies, regulatory timelines, and systemic interpretations that revive the deep civic ties between construction norms, insurance origins, and volunteer emergency response. His work is a tribute to: The adaptive evolution of Building Codes and Safety Regulations The foundational models of Early Insurance and Mutual Aid Systems The spatial tensions of Urban Density and Infrastructure The civic legacy of Volunteer Fire Brigades and Response Teams Whether you're an urban historian, policy researcher, or curious explorer of forgotten civic infrastructure, Toni invites you to explore the hidden frameworks of urban safety — one regulation, one risk pool, one volunteer brigade at a time.