Accessibility codes have transformed from basic guidelines into comprehensive frameworks that shape how we design, build, and experience the world around us today.

🌍 The Foundation: Understanding Accessibility Codes and Their Purpose

Accessibility codes represent far more than bureaucratic regulations or compliance checkboxes. These frameworks embody society’s commitment to ensuring that every individual, regardless of physical ability, sensory capability, or cognitive difference, can navigate and participate fully in public and private spaces. The evolution of these codes reflects our growing understanding that true inclusivity requires intentional design and systematic implementation.

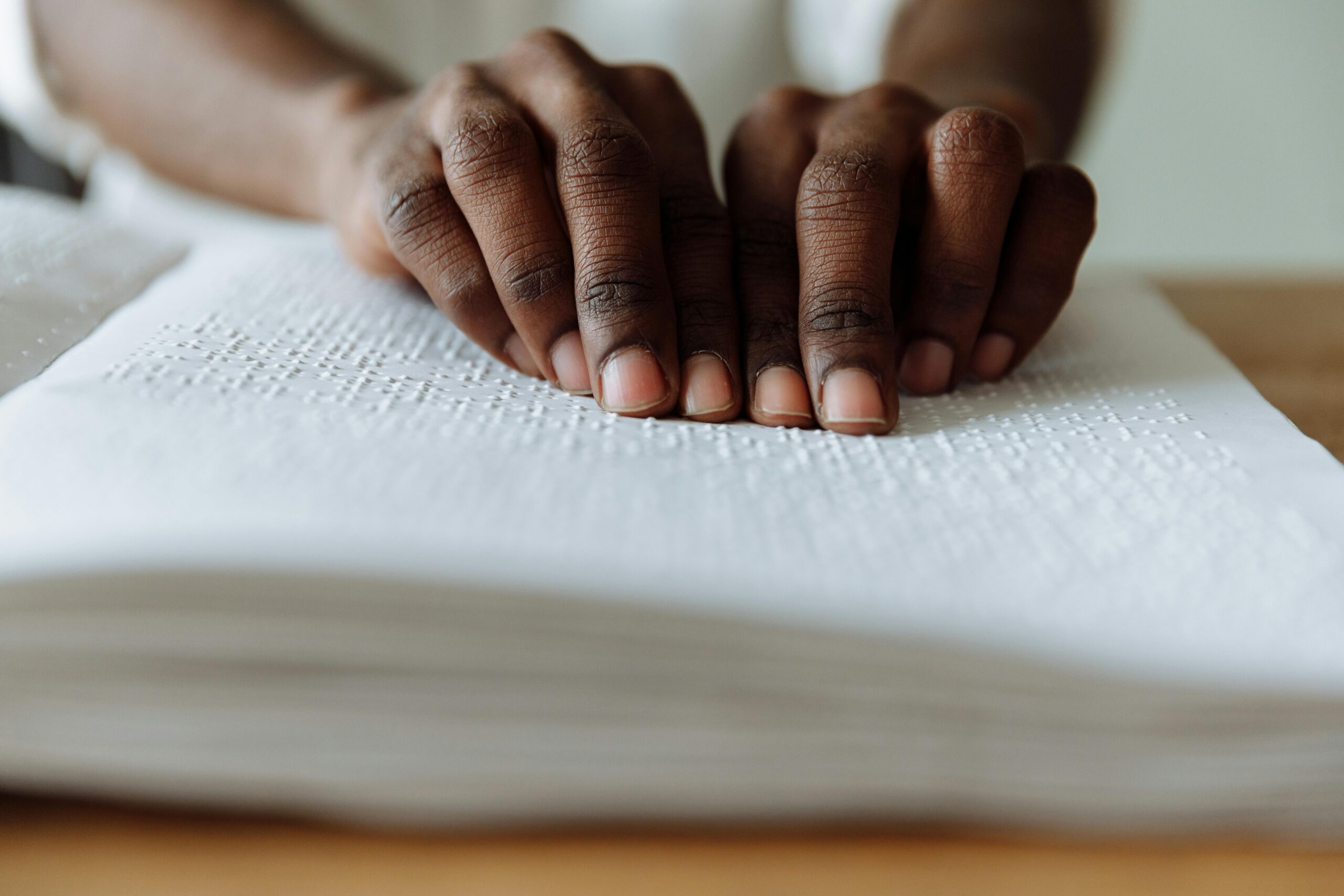

At their core, accessibility codes establish minimum standards for removing barriers that prevent people with disabilities from accessing buildings, transportation, communication, and digital environments. They address physical obstacles like stairs without ramps, narrow doorways, and inaccessible restrooms, while also tackling less visible barriers in digital interfaces, signage systems, and communication methods.

The impact of these regulations extends far beyond the disability community. Universal design principles embedded in modern accessibility codes benefit parents with strollers, elderly individuals, delivery workers, and anyone temporarily injured. This broader applicability demonstrates that accessible design is simply good design for everyone.

📜 From Architectural Barriers Act to Global Standards

The journey toward comprehensive accessibility codes began earnestly in the 1960s and 1970s when disability rights activists challenged systemic exclusion from public life. The Architectural Barriers Act of 1968 in the United States marked a watershed moment, requiring federal buildings to be accessible to people with physical disabilities. Though limited in scope, it established the precedent that accessibility was a right, not a privilege.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 revolutionized accessibility standards by extending protections across employment, public services, public accommodations, and telecommunications. The ADA Standards for Accessible Design provided specific technical requirements for elements like parking spaces, ramps, elevators, and restroom facilities. This comprehensive approach influenced legislation worldwide, inspiring similar frameworks in Canada, Australia, the European Union, and beyond.

International collaboration through organizations like the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has helped harmonize accessibility standards globally. ISO 21542, for example, provides guidelines for accessible and inclusive building design that transcend national boundaries, facilitating consistent expectations for multinational corporations and international travelers.

The Digital Revolution and Web Accessibility

As society shifted online, accessibility codes expanded to address digital environments. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), first published in 1999 and regularly updated since, established standards for making websites, applications, and digital content accessible to people with visual, auditory, motor, and cognitive disabilities.

WCAG principles—perceivable, operable, understandable, and robust—guide developers in creating digital experiences that work with assistive technologies like screen readers, voice recognition software, and alternative input devices. Many countries have incorporated WCAG into their legal frameworks, making digital accessibility a enforceable requirement rather than a voluntary best practice.

🏗️ Built Environment: Creating Spaces That Welcome Everyone

Contemporary accessibility codes address every aspect of the built environment with remarkable specificity. Minimum doorway widths of 32 inches accommodate wheelchairs and mobility devices. Ramp slopes limited to 1:12 ratios ensure safe navigation for people using wheeled mobility aids. Grab bars positioned at precise heights in restrooms provide necessary support.

But modern codes go beyond these fundamentals. They address sensory considerations like acoustics for people with hearing impairments, lighting quality for those with visual disabilities, and tactile indicators for wayfinding. Color contrast requirements ensure signage remains legible for people with low vision, while braille and raised lettering provide alternative information channels.

Parking accessibility extends beyond designated spaces with the familiar wheelchair symbol. Codes now specify van-accessible spaces with additional clearance, proper slopes to prevent water accumulation, and proximity to accessible building entrances. Loading zones accommodate passengers who need extra time or assistance during transfers.

Vertical Accessibility and Circulation

Elevators represent critical access points in multi-story buildings, and accessibility codes detail their design extensively. Requirements cover button height and tactile markings, auditory signals announcing floors, door opening width and timing, interior dimensions accommodating wheelchairs, and emergency communication systems accessible to deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals.

Stairways, while not accessible to everyone, incorporate safety features benefiting all users: consistent riser heights and tread depths, continuous handrails extending beyond top and bottom steps, tactile warnings at stair beginnings, and adequate lighting. Platform lifts and limited-use elevators provide alternatives where full elevators are impractical.

💻 Digital Accessibility: Building the Inclusive Internet

Digital accessibility has emerged as perhaps the most rapidly evolving aspect of accessibility codes. As essential services migrate online—banking, healthcare, education, government services, employment—digital barriers translate directly into social and economic exclusion.

Modern accessibility codes require that websites and applications provide alternative text for images, enabling screen reader users to understand visual content. Video content must include captions for deaf users and audio descriptions for blind users. Interactive elements need keyboard accessibility for people who cannot use pointing devices. Forms require clear labels and error messages that assistive technologies can interpret.

Color cannot be the sole means of conveying information, as colorblind users would miss crucial details. Text must be resizable without breaking layouts. Flashing content must be carefully controlled to prevent triggering seizures in people with photosensitive epilepsy. These requirements collectively ensure that digital experiences remain functional regardless of how users access them.

Mobile Applications and Emerging Technologies

Smartphone accessibility features have revolutionized independence for people with disabilities. Screen readers, voice control, switch access, and customizable displays enable diverse interaction methods. Accessibility codes increasingly address mobile-specific considerations like touch target sizes, gesture alternatives, and orientation flexibility.

Emerging technologies like virtual reality, augmented reality, and artificial intelligence present new accessibility challenges and opportunities. Forward-thinking accessibility frameworks are beginning to address how these technologies can be designed inclusively from inception rather than retrofitted later.

🚌 Transportation: Connecting Communities Accessibly

Transportation accessibility determines whether people with disabilities can work, socialize, access healthcare, and participate in community life. Comprehensive accessibility codes address public transit systems, paratransit services, pedestrian infrastructure, and increasingly, ride-sharing platforms.

Buses must feature low floors or lifts, securement systems for wheelchairs, priority seating, auditory and visual stop announcements, and accessible fare payment systems. Train and subway stations require elevators or ramps to platforms, tactile platform edges preventing dangerous falls, gap mitigation between platforms and trains, and accessible ticketing machines.

Pedestrian infrastructure receives growing attention in accessibility codes. Curb cuts at intersections benefit wheelchair users, parents with strollers, and rolling luggage users alike. Accessible pedestrian signals with auditory tones help blind pedestrians cross safely. Sidewalk width and surface quality standards ensure usability for mobility device users.

Autonomous Vehicles and Future Mobility

Self-driving vehicles present tremendous potential for transportation independence, particularly for people who cannot drive conventional vehicles due to visual or physical disabilities. Progressive accessibility codes are beginning to establish requirements ensuring autonomous vehicles accommodate diverse passengers, with accessible entry/exit systems, onboard communication interfaces, and trip planning tools.

🎓 Educational Environments: Learning Without Barriers

Educational accessibility codes ensure students with disabilities can access learning opportunities equally. Beyond physical accessibility in classrooms and laboratories, these frameworks address instructional materials, assessment methods, and educational technology.

Digital textbooks must be compatible with assistive technologies. Video lectures require captions and transcripts. Online learning platforms need keyboard navigation and screen reader compatibility. Science laboratories require adjustable-height work surfaces and accessible safety equipment. These accommodations benefit students with permanent disabilities and those with temporary injuries or situational limitations.

🏥 Healthcare Facilities: Accessible Wellness and Treatment

Healthcare accessibility carries life-or-death implications. Accessibility codes for medical facilities address examination tables and chairs that transfer patients safely, diagnostic equipment accommodating people with mobility limitations, accessible weight scales for wheelchair users, and communication systems for deaf and hard-of-hearing patients.

Medical communication represents a critical accessibility component often overlooked in traditional building codes. Requirements for qualified interpreters, accessible patient portals, and alternative format medical documents ensure patients understand diagnoses, treatment options, and care instructions regardless of sensory or cognitive disabilities.

⚖️ Enforcement, Compliance, and Cultural Shift

Accessibility codes succeed only through effective enforcement and compliance mechanisms. Many jurisdictions require accessibility plans during permitting processes, inspections verifying code compliance before occupancy, and complaint procedures for addressing violations. Financial penalties and legal liability motivate compliance, but increasingly, businesses recognize accessibility as good practice benefiting brand reputation and market reach.

The disability market represents significant economic power. People with disabilities and their families make purchasing decisions influenced by accessibility. Companies embracing accessibility tap this market while demonstrating corporate social responsibility valued by consumers broadly.

Training and Awareness

Implementing accessibility codes effectively requires training architects, builders, developers, content creators, and service providers. Professional certification programs in universal design and accessibility specialization are growing. Educational institutions increasingly incorporate accessibility principles into architecture, engineering, computer science, and design curricula.

🌟 Innovation Driven by Accessibility Requirements

Accessibility codes drive innovation benefiting everyone. Voice-activated assistants developed for people with mobility impairments now serve millions in hands-free situations. Automatic doors installed for wheelchair access convenience parents, delivery workers, and elderly individuals. Captioning developed for deaf viewers helps language learners, people in noisy environments, and those watching videos silently.

Eye-tracking technology, initially developed for people with severe motor disabilities, finds applications in marketing research, pilot training, and surgical procedures. Curb cuts benefit cyclists, skateboarders, and wheeled luggage users. High-contrast displays assist users in bright sunlight. These examples demonstrate that accessible design generates cascading benefits throughout society.

🔮 Future Directions: Anticipating Tomorrow’s Accessibility Needs

Accessibility codes continue evolving to address emerging challenges and opportunities. Artificial intelligence and machine learning offer tremendous potential for personalized accessibility features—interfaces that adapt automatically to individual user needs, real-time translation services, and predictive text improving communication for people with cognitive disabilities.

Smart cities integrating sensors, data analytics, and connected infrastructure could revolutionize accessibility. Imagine sidewalks reporting surface damage automatically, traffic signals adjusting timing based on pedestrian mobility speeds, and public transit providing real-time accessibility information about crowding, equipment status, and route disruptions.

Climate change and environmental sustainability intersect increasingly with accessibility codes. Extreme weather events disproportionately impact people with disabilities who may have limited evacuation options. Green building practices must incorporate accessibility from inception rather than treating them as competing priorities.

Cognitive and Invisible Disabilities

Future accessibility frameworks must better address cognitive and invisible disabilities often overlooked in traditional codes focused on physical and sensory impairments. Requirements for clear wayfinding, reduced sensory overload, quiet spaces in public buildings, and plain language in documents and interfaces will expand.

Mental health considerations are gaining recognition, with accessibility codes beginning to address environmental factors affecting psychological wellbeing. Biophilic design incorporating natural elements, spaces offering visual privacy, and noise control measures benefit people with anxiety, autism, and sensory processing differences.

🤝 Collective Responsibility for an Inclusive Future

Creating truly barrier-free environments transcends regulatory compliance. It requires cultural transformation recognizing disability as natural human diversity rather than deficit. Accessibility codes provide frameworks, but meaningful inclusivity emerges from genuine commitment to equity and participation.

Involving people with disabilities in design processes from inception ensures solutions address real needs rather than imagined ones. “Nothing about us without us” remains the disability community’s rallying cry, emphasizing that lived experience must inform policy and implementation.

Technology democratizes accessibility advocacy. Social media amplifies voices highlighting barriers and celebrating inclusive design. Digital platforms enable collaboration across geographical boundaries, sharing best practices and pressuring organizations to prioritize accessibility.

Businesses increasingly recognize that accessibility expands their customer base, improves employee satisfaction and retention, reduces legal risk, and enhances brand reputation. This business case complements moral and legal imperatives, creating multiple motivations for embracing accessibility proactively.

🎯 Moving Beyond Minimum Standards

While accessibility codes establish essential baselines, truly inclusive design aspires beyond minimum compliance. Leading organizations pursue universal design excellence, creating experiences that delight diverse users rather than merely accommodating them grudgingly.

This excellence manifests in seamless integration where accessibility features don’t segregate or stigmatize users. Everyone benefits from clear signage, comfortable seating, intuitive interfaces, and flexible interaction methods. Inclusive design becomes invisible—simply good design that works for everyone.

The evolution of accessibility codes reflects our society’s progress toward recognizing and valuing human diversity. From the Architectural Barriers Act to comprehensive digital accessibility requirements, these frameworks have expanded in scope and sophistication. Yet our work remains unfinished. Emerging technologies, changing demographics, and evolving understanding of disability require continuous adaptation and improvement.

The barrier-free world envisioned by accessibility advocates depends on sustained commitment from governments enacting and enforcing strong codes, businesses investing in inclusive design, professionals developing accessibility expertise, and individuals advocating for themselves and others. Together, these efforts unlock true inclusivity where everyone can participate fully in community life, regardless of ability. The journey continues, but the direction is clear—toward a world designed for everyone from the start. ♿✨

Toni Santos is a regulatory historian and urban systems researcher specializing in the study of building code development, early risk-sharing frameworks, and the structural challenges of densifying cities. Through an interdisciplinary and policy-focused lens, Toni investigates how societies have encoded safety, collective responsibility, and resilience into the built environment — across eras, crises, and evolving urban landscapes. His work is grounded in a fascination with regulations not only as legal frameworks, but as carriers of hidden community values. From volunteer firefighting networks to mutual aid societies and early insurance models, Toni uncovers the structural and social tools through which cultures preserved their response to urban risk and density pressures. With a background in urban planning history and regulatory evolution, Toni blends policy analysis with archival research to reveal how building codes were used to shape safety, transmit accountability, and encode collective protection. As the creative mind behind Voreliax, Toni curates historical case studies, regulatory timelines, and systemic interpretations that revive the deep civic ties between construction norms, insurance origins, and volunteer emergency response. His work is a tribute to: The adaptive evolution of Building Codes and Safety Regulations The foundational models of Early Insurance and Mutual Aid Systems The spatial tensions of Urban Density and Infrastructure The civic legacy of Volunteer Fire Brigades and Response Teams Whether you're an urban historian, policy researcher, or curious explorer of forgotten civic infrastructure, Toni invites you to explore the hidden frameworks of urban safety — one regulation, one risk pool, one volunteer brigade at a time.